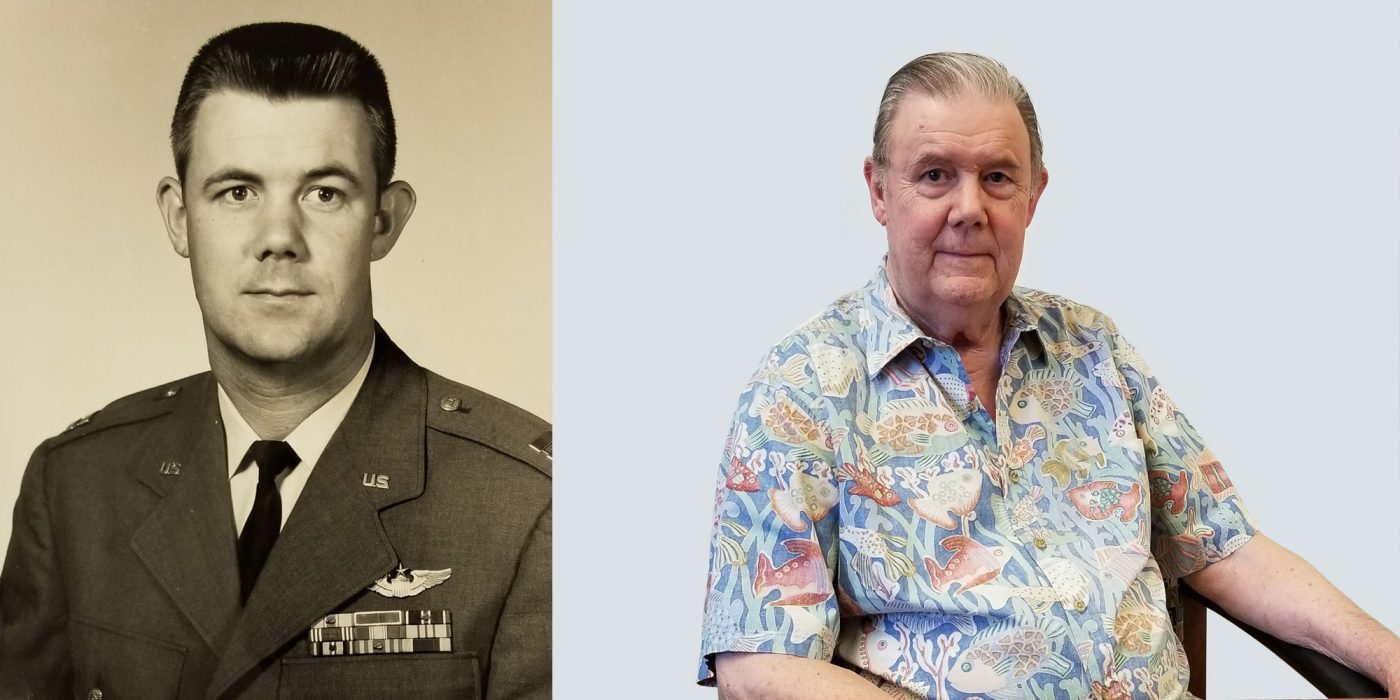

JIM THOMAS

“Piloting in War and Peace”

Decorated former U.S. Air Force Officer/Pilot who served before and during the Vietnam War.

Jim was born in 1935 in Everett, Washington (26 miles North of Seattle). His father, Jim Sr., was a journalist and worked for the Associated Press (AP) in Seattle. His mother was both a homemaker and seamstress who designed costumes for the Seattle area theater community.

In the summer of 1943, the AP transferred Jim’s father to their San Francisco office. With World War II going on housing was scarce in the city so his family, which included Jim’s younger brother David, moved to San Mateo, just 20 miles south. In the summer of 1945, after the war ended, Jim’s family moved into the city of San Francisco.

Jim finished his high school and College years while living in San Francisco. In 1953, at age 18, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve. His commanding officer was a WWII Colonel and pilot who just happened to be a senior Captain with Pan American World Air ways, flying out of SFO. As a result, Jim became very interested in aviation and in 1955 started taking flying lessons in floatplanes out of Sausalito; this permanently changed his life. Perhaps he was born to fly since his birthplace, Everett, Washington, was the home of the Boeing Aircraft Company.

T-34

T-28

B-25

In July 1956, Jim was accepted into the U.S. Air Force pilot training program. His flight training was done in Georgia flying the T-34 and T-28 aircraft and in Texas flying the B-25 aircraft. Upon graduation in October 1957, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant and awarded his pilot wings. He now had 250 flying hours. His father had died a few months earlier so he wanted to be stationed as close as possible to his mother and a younger brother who still lived in San Francisco.

Jim was very fortunate to be assigned to MATS (Military Air Transport Service) at Travis AFB, Fairfield, CA which was just 48 miles northeast by car from San Francisco. He had asked to fly the Douglas C-124 Globemaster (affectionately called “Old Shakey”) a four-engine propeller transport, one of the largest planes in the world at the time. His training was completed at West Palm Beach AFB in Florida. He returned to Travis AFB in January 1958 and began flying both cargo and passenger missions worldwide.

The C-124 was normally crewed by seven people: two pilots (a Second or First Pilot and an Aircraft Commander) one Navigator, two Flight Engineers, and two Loadmasters. Sometimes the crew was augmented with an extra pilot and navigator.

Jim spent the next two years flying and gaining experience as he worked his way up from Second to First Pilot and on to Aircraft Commander (AC). MATS required an Aircraft Commander to have a minimum of 2,000 flying hours.

Jim’s flights, or missions as they were called, could be worldwide but were mostly westward from California throughout the Pacific and into Japan and Southeast Asia. The C-124 was a slow airplane cruising at 205 Knots TAS (true airspeed) and low flying (below 10,000 feet) because it was not pressurized like our planes today. This meant that a flight from Travis AFB, CA to Hickam AFB in Honolulu, a distance of about 2070 nm, would take about 10.5 hours on average (no wind). Flight crews had to island-hop across the Pacific since the distances were so great and the airplane was so slow. They would crew rest for 12 to 15 hours after each flight landed then continue on the next day. The weather over the southern routes through Hawaii, Wake, Guam, and the Philippines was usually very good. However, flights over the northern routes through Seattle, Anchorage, Shemya Island (near Russia) and on to Japan were a different story, especially during the winter months. Many times, they were flying in the clouds and on instruments for the majority of the flights.

C-124

Jim landed the C-124 a number of times at Shemya Air Force Station in Zero/Zero conditions, meaning that the clouds or fog were at ground level and there was no forward visibility from the cockpit; you could not see the airport or the runway at all. You had to rely totally on the GCA (ground-control approach) radar controller to guide you to the exact landing spot. You did not know you were on the ground until you felt the main landing gear touch the runway and then you could not see to taxi; you must stop on the runway and wait for the “follow me” truck to find you and guide you to the parking ramp. Needless to say, you had better be an excellent instrument pilot and have total confidence in the GCA controllers, which were some of the best in the world.

C-124

On 12 February 1960, while flying the C-124 eastbound at 9,000 feet in VFR conditions, from the island of Guam to Wake Island, a distance of 1,300 nm, with a flight time of just over 6.5 hours and having past the half-way or ETP (equal time point) Jim’s aircraft suffered a sudden fire on the #3 engine. Emergency procedures were followed and the engine was quickly shut down, but the fire did not go out. They dived the aircraft to gain speed in order to blow the fire out; it finally extinguished, but in the process, the aircraft had also lost total electrical power on an airplane that was heavily dependent on electrics. This was very bad since now there was no radio communication or navigation equipment available, no propeller controls, no normal fuel tank transfer to the engines, no flight instruments, no compass system, and on and on it went.

There had been no time to send off a MAYDAY emergency message or to radio their trouble or position to the outside world. They were on their own and alone.

The crew had about 2.5 hours to fly before reaching Wake Island and about 3.5 hours of fuel onboard. What if they could not find the island? Without the ability to navigate properly, where would they be in another 2.5 hours? Wake was a very small coral atoll completely alone in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with no islands around it within a thousand miles, except to its south.

They knew that the winds could easily change and blow them off course in any direction and unless they found Wake Island, they would run out of fuel and have to ditch the airplane in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Therefore, they needed to turn southeast towards the Marshall Islands where there might be more places to land. Fortunately, the weather was good, they were flying in daylight conditions and out of the clouds, but their navigator only had the sun and the little standby “whiskey” compass with which to navigate. Would that be enough?

After a few minutes, their navigator came up with a possible solution. On his charts and using the sun as reference, he plotted a north/south line of position (LOP) over the island of Kwajalein, which was southeast of them in the Marshall Islands and 700 nm south of Wake.

Kwajalein had an adequate runway and was operated by the U.S. Navy. The navigator said there was a 50/50 chance of them finding the island if they turned about 45 degrees to the southeast, to a heading of about 135 degrees. They knew that when they crossed that LOP they had to turn either north or south and follow it until they crossed over the Island. If they guessed wrong, they would run out of fuel and have to ditch. There would be no chance of a rescue.

They decided they needed to be well south of Kwajalein when they intercepted the LOP and then they could turn north and have a good chance of sighting the island. They turned to a heading of 135 degrees and felt confident it would do the job.

They had completed the many required emergency procedures earlier and now reviewed and thoroughly discussed the C-124 ditching procedures to be used if necessary.

They flew on for what seemed a long time and eventually crossed the LOP. They calculated the odds and turned north following the line. They flew and waited with as many eyes looking out as possible hoping to catch a glimpse of the island.

Jim said, “I was starting to feel like Amelia Earhart must have felt back in 1937 when she and her navigator Fred Noonan were lost at sea trying to find Howland Island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean”.

Jim and the crew of his C-124 Globemaster had used their combined aviation wisdom and had committed to this course of action. Now all they could do is wait and hope.

Jim said, “Just when I was beginning to believe we were lost and it might be hopeless, I raised my head up once again from scanning the instrument panel and I looked out the cockpit windows. I caught a glimpse of something different; it was not the usual miles and miles of Open Ocean that we had been watching for the last six-plus hours. Just between some parting clouds ahead and below us something different caught my eye. It was right in front of us, that wonderful, God-forsaken, little coral atoll called Kwajalein. A big cheer went up; we would not be Shark bait after all”.

However, there was one more thing they had to do before they could relax and that was to land the airplane. Kwajalein had only one runway just 5000 feet long (which was the normal minimum length for a C-124 landing). It had to be a one-shot approach and landing. A missed approach or a go-around was impossible since they had one engine out and no control of the three propellers. Landing would be faster than normal since they were unable to lower the wing flaps to slow the landing speed. The good news was that they could manually lower the landing gear.

Some red flares were fired to alert the Navy of their emergency. They landed uneventfully and became a guest of the U.S. Navy for a few days while the Air Force flew in parts and mechanics from Hickam AFB, Hawaii, to repair their airplane.

Of course, the aircrew wanted to know what had caused the #3 engine fire and the total loss of electrical power. The engine fire was easy to diagnose; the mechanics said it was caused by a leaking fuel line on the #3 engine. The loss of electrical power was caused by a total break in the main power cable behind the flight engineers panel. This cable supplied the power from the four engine-driven generators to the flight deck to be controlled as necessary by the flight engineer.

The repairs were going to take longer than expected so Jim’s crew was flown back to Hickman AFB on another Air Force plane. They later learned that the break in the main electrical cable was most likely caused by years of aircraft vibration, electrolysis action and corrosion.

Saving their aircraft and crew had been a total team effort. Six months later at their home station, Travis AFB, California, the Air Force awarded each of the seven crewmembers the Air Force Commendation Medal for meritorious achievement.

On 22 June 1960, while flying a C-124 westbound at 8,000 feet in VFR daylight conditions from the island of Guam to Clark Air Base (North of Manila) in the Philippines, a distance of 1390 nm, with a flight time of 7 hours and having passed the ETP (equal time point) Jim’s aircraft suffered a sudden and total loss of electrical power.

Like his earlier emergency in February of the same year, there had been no time to send off a MAYDAY emergency message or to radio their trouble or position to the outside world. They were left with no radio communications or navigation equipment, no propeller controls, inability to normally transfer fuel from the wing tanks to the engines, no flight instruments, no compass system, etc.

They had no choice but to continue flying towards their destination. There was only the ocean ahead for hours until they would cross some part of the Philippine islands.

They decided that if they were lucky enough to cross Manila Bay they might be able to land at Sangley Point NAS (Naval Air Station) which was right on the bay at sea level, in a very open, non-mountainous area. They should have plenty of daylight left for landing. They flew on for hours; the wind gods were good to them and they finally saw Manila dead ahead.

Sangley Point NAS was clearly in view. They had no radio communication with anyone on the ground, so Jim had one of the flight engineers fire several red flares from a port in the top of the flight deck to indicate they were in trouble and declaring an emergency. He slowed the aircraft down and began circling the airfield, starting at 8,000 feet, and then descending in a left-hand circular pattern until he arrived on the final approach lined up with the runway.

Even though the runway was 8,000 feet long, it had water at both ends. Their approach and landing speeds would be much higher than normal since they could not lower the wing flaps. They had no control of the propellers (therefore a missed approach would be impossible); as for braking, there would be no propeller reversing to aid in stopping. It would have to be a one-shot approach and landing.

On short final approach they got the green light signal to land from the tower (although it really did not matter; they were committed to land anyway). It all worked out well. Jim said he planted that baby so hard on the runway that all four main gear tires blew out on impact. The Navy personnel working around there said they thought a bomb went off.

Jim was able to taxi the aircraft a few yards and vacate the active runway. He parked the aluminum monster and contacted the necessary personnel at Clark AFB up the road a ways. They must have been delighted to hear that he wrecked another C-124.

In April 1961, the Air Force awarded Jim his second Air Force Commendation Medal for meritorious achievement.

In early 1962, Jim, who was still stationed at Travis AFB, was selected to fly the new Boeing C-135B jet transport, which was the military version of the Boeing 707. His training was provided by the Strategic Air Command (SAC) flying their KC-135 refueling tanker aircraft since MATS did not have their own C-135 training program yet. The C-135 was very similar to the KC-135 minus all the aircraft refueling equipment. The training for ground school and simulator was done at Castle AFB in CA; the flying training was done at Walker AFB in Roswell, NM.

At Roswell, each SAC instructor pilot had two students for flight training. Jim was one; the other was a SAC pilot. However, the difference was the SAC pilot remained in SAC after training and Jim went back to his MATS squadron at Travis AFB.

B-52 KC-135

Each training mission lasted for four hours with each student flying for two hours. When the SAC student was flying and it came time to refuel other aircraft, Jim could leave the cockpit, go to the rear and watch the boom operator as he refueled the big B-52 bombers or the assorted fighters, who were also training their pilots

Jim finished his training with SAC and returned to Travis AFB. His squadron, the 44 ATS, was just receiving the brand new C-135B models from Boeing. These were beautiful airplanes with larger, more powerful engines than the C-135A plus they had engine thrust reversers and all the latest modifications.

It was a huge transition to go from a low and slow flying four-engine propeller plane like the C-124 to a very fast, high-flying four-engine jet aircraft like the C-135B, however, it was a lot of fun and much simpler to fly. The normal flight crew was six for regular missions around the world.

C-135

In November 1963, Jim was the AC on an westbound cargo flight from Germany to McGuire AFB, NJ. While flying a C-135A at 35,000 feet and some 430 nm east of Canada, his aircraft experienced a complete electrical power failure. They were about an hour from any landfall and darkness was fast approaching. Similar to his two earlier C-124 emergencies in 1960, they had lost all radios and navigation equipment, etc., including their IFF (identification-friend or foe) aircraft transponder (which would allow military and civilian air traffic controllers to identify them). The C-135 did have one very nice feature; it had a small emergency generator, which worked off hydraulic pressure. However, you needed to turn it on before you lost all electrical power. It provided enough power to run some essential flight instruments and one short-range UHF radio, which had a range of about 150 miles at that altitude. Fortunately, Jim had turned the generator on just as the electrical power was failing.

As they approached Canadian airspace, still at 35,000 feet, they started broadcasting a MAYDAY (emergency) message in the blind. They needed to land the airplane before total darkness set in, since the aircraft had no exterior or interior lights, including landing lights and they were headed into one of the busiest air traffic corridors in North America without adequate radio and navigation equipment.

With darkness approaching and the loss of essential aircraft equipment, things were starting to look a little grim when all of a sudden a voice was heard over their UHF radio. It said, “MATS 328 this is the Canadian Air Force, we hear your MAYDAY call, do you read?” Jim’s response was essentially, “This is MATS 328, we read you, can you help us”? After explaining his problems, Jim asked to be directed to the nearest suitable airport. The controller then vectored them to the Canadian Air Force Base at Goose Bay, Labrador. They made an uneventful landing in the dark with only the runway lights as a guide.

The next day the U.S. Air Force flew in some mechanics to Goose Bay to examine the C-135; the repairs were going to take longer than expected so Jim’s crew was airlifted back to McGuire AFB, NJ.

On 25 May 1964, Jim was the (IP) instructor pilot conducting a training flight from Travis AFB in a C-135A aircraft. While flying at 35,000 feet fifteen miles west of Ukiah, CA, at approximately 1800 PST, a loud explosive sound was heard accompanied by a shuddering of the aircraft and a sharp kick of the #3 throttle lever. The #3 engine firelight came on and the fire switch was pulled to shut the engine down. The engine by this time had frozen and the fire warning light had gone out. All four engine throttles were pulled to idle and the aircraft began to slow down.

Jim, the (IP) was sitting in the copilot’s seat at the time and could look out the right window. He observed that the #3 jet engine had exploded and that forward parts of the engine were missing with the rear of the engine hanging down sharply from the right-wing. The #4 engine showed some external damage to its left side, but according to the engine instruments, it was still running. There was also some damage to the leading edge of the right-wing.

Jim took control of the aircraft from the right seat. Appropriate emergency procedures were followed then he made a call to air traffic control and explained their situation. He was given immediate clearance to descend and fly directly to Travis AFB.

Jim’s crew on that flight consisted of himself and two student pilots; one was a second lieutenant recently out of pilot training, the other was a very seasoned RAF officer from England who was learning to fly the C-135 as part of an exchange program with the United States. In addition, there was one instructor flight engineer and two of his students.

Jim ordered the new lieutenant, who had been flying the aircraft from the pilot’s seat, to switch positions with the RAF officer who had been sitting in the observer seat. He now had the most experienced pilots in the best positions in the event things got worse.

Jim began a slow descent and headed back to Travis AFB. There was no way to know the extent of the damage until after landing, so they had to assume the worst and to be very cautious as they maneuvered the airplane.

In order to lighten the airplane weight and be able to land at a slower speed, which was desirable, Jim got approval from air traffic control to dump 30,000 pounds of extra jet fuel. They finished the fuel dumping as they reached about 12,000 feet above the ground.

At that altitude, Jim began various controllability checks to see how the airplane handled and if it could be landed safely. He found that a wing flap setting of 20 degrees along with normal approach speeds was completely safe. There had been some slight and continuous buffeting which started after the explosion, but this did not seem to matter much.

The landing at Travis AFB was uneventful. The airplane was stopped just clear of the runway and the remaining engines were shut down. The airplane was then towed to the hanger area. Quite a crowd had assembled. Jim and his crew walked around the exterior and observed the damage to the #3 and #4 engines, the right-wing, the fuselage, and the tail. Parts from #3 engine had been thrown everywhere. Fortunately, no serious damage had been done to the essential systems or flight controls.

After several months, a report arrived explaining the cause of the #3 engine explosion. It was determined that during the previous engine overhaul at the Air Force facility in Sacramento, CA, one of the fan blades in the forward fan section of #3 engine had not been secured properly. Over time, this blade worked its way out of its retaining slot and while the engine was rotating at high speed, it violently separated from the engine.

C-141

In December 1964, Jim was transferred to Tinker AFB, near Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, to serve as an Instructor Pilot on the new C-141 four-engine jet transport built by Lockheed Aircraft.

Jim, like the students he would instruct, first had to complete the C-141 ground school, simulator and flight-training program at Tinker AFB. Thereafter, his job along with the other instructors was to teach and qualify pilots (new and old) to fly the C-141 aircraft.

He spent the next three years in this local assignment although he and the other instructors did fly occasional stateside and overseas trips to stay familiar with the MATS global operations. On January 1, 1966, the Air Force changed the name of MATS to MAC (Military Airlift Command).

C-141

In early August 1967, while still stationed at Tinker AFB, he was informed that he was soon to be promoted to the rank of Major. If he accepted the promotion this meant he would have to agree to remain on active duty for several more years. After much thought, and although he had 10 years of active Air Force service behind him, he decided to forgo the promotion, to resign his regular Air Force commission as a Captain, and to begin a new career as an Airline Pilot.

In late August 1967, Jim said his goodbyes to the Air Force and his friends. In early September, he found himself sitting in a classroom in San Diego, CA, learning to fly the Boeing 727 aircraft as a First Officer for PSA (Pacific Southwest Airlines).

During Jim’s military flying career between 1957 and 1967, he flew a great many missions throughout the world. These missions included transporting both military and civilian personnel, their equipment, cargo of all types, weapons, and explosives as well as evacuating the sick and wounded to various regional and stateside hospitals and returning deceased military members to the U.S. In addition, he flew weather reconnaissance, search and rescue and all types of humanitarian and military missions in support of the United Nations.